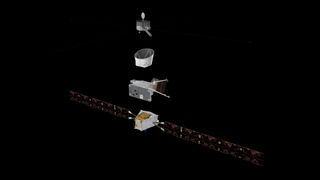

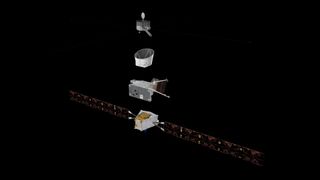

The joint European-Japanese BepiColombo spacecraft is set for a Mercury flyby late on Wednesday (Sept. 4), but thruster issues mean the probe faces a lengthy delay before entering orbit around the solar system’s innermost planet.

BepiColombo launched in 2018 on an Ariane 5 rocket to seek out answers to mysteries surrounding Mercury. Its circuitous route to entering orbit around Mercury involves one Earth flyby, a pair of Venus flybys and six more around Mercury itself. The Sept. 4 flyby will be BepiColombo’s fourth of Mercury to date.

However, plans for the upcoming maneuver have been revised due to the spacecraft’s thrusters no longer operating at full power, due to a glitch experienced in April this year. Engineers have since identified unexpected electric currents between BepiColombo‘s Mercury Transfer Module (MTM) solar array and the unit responsible for extracting power and distributing it to the rest of the spacecraft.

“Following months of investigations, we have concluded that MTM’s electric thrusters will remain operating below the minimum thrust required for an insertion into orbit around Mercury in December 2025,” the European Space Agency’s (ESA) BepiColombo mission manager, Santa Martinez, said in a Sept. 2 statement.

Related: BepiColombo: Exploring Mercury, the least visited planet of the inner solar system

Fortunately, the issue will not threaten the mission’s chances of success over the long haul. ESA’s Flight Dynamics team devised a workaround to counter the spacecraft’s reduced thrust and still maintain the baseline scientific mission at Mercury by planning a new trajectory. The newly devised maneuver will see BepiColombo fly about 22 miles (35 kilometers) closer to the planet than originally planned, reducing the thrust requirements for the fifth flyby. The sixth flyby will then see the spacecraft embark on its new trajectory.

With this new trajectory, BepiColombo is now expected to arrive at Mercury in November 2026, the ESA statement noted.

RELATED STORIES:

BepiColombo carries a suite of 16 instruments across two orbiters, one each developed by ESA and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA). The two will separate and spend a year in orbit studying Mercury. This science phase could be extended to a second year.

“We get to fly our world-class science laboratory through diverse and unexplored parts of Mercury’s environment that we won’t have access to once in orbit, while also getting a head start on preparations to make sure we will transition into the main science mission as quickly and smoothly as possible,” said Johannes Benkhoff, BepiColombo project scientist.

BepiColombo’s main science camera is shielded until the ESA and JAXA orbiters separate. However, three MTM monitoring cameras (M-CAMs) will snap images of the heavily cratered surface of Mercury during the upcoming flyby.